Look around. Within the halls of BVNW, a considerable number of students sport $98 Lululemon leggings, $180 Adidas Ultra Boosts or simply drown out their surroundings with $165 Apple AirPods. This image fuels the stereotype that paints those at BVNW as well-off.

However, not all of its students are endowed with such privilege.

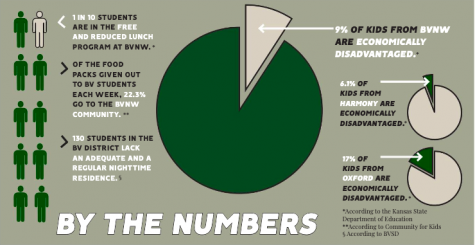

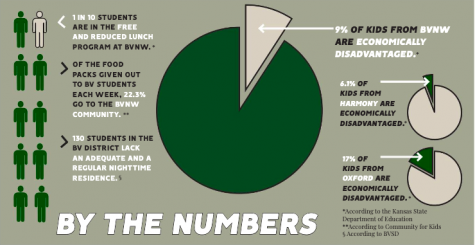

According to the Kansas State Department of Education, Blue Valley schools do house a number of financially struggling students. At BVNW, as many as one out of every 10 students are cash-strapped. When looking at Northwest’s feeder schools, the Harmony Middle School has a student population of 6.1 percent economically disadvantaged students while Oxford Middle School is 17 percent.

These statistics often fail to be noticed by the overwhelming number of upper middle class and upper class population, junior Naomi James said, many of whom have yet to witness economic disadvantage firsthand.

“A lot of students, at least at Northwest, tend to sort of naturally segregate themselves almost based on their financial status with their families,” James said. “I think because most of the wealthier kids and more upper middle class kids all hang out with each other, a lot of times they don’t see the struggle [others go through].”

James said her family has never experienced striking financial challenges, but she knows people close to her who have.

On multiple occasions James said she has purchased extra food from the cafeteria for her friends using the free and reduced lunch program. To receive this lunch option, families with low yearly incomes can apply through the Blue Valley district website. According to the Kansas Department of Education, there are 1831 students approved for free or reduced-price lunches district-wide and 148 students approved at Northwest, the second highest number in the district.

The situation becomes an issue when the student is still hungry after their meal, James said, and other options are scarce. James’ first experience of paying for a friend’s lunch opened her eyes to the reality of financial inequality in the Blue Valley district, she said. In the midst of a community where it seems that every other person has the latest iphone and designer clothing, those without such amenities feel alienated, James said.

In the past six years, the district has experienced a rise in the number of economically disadvantaged students, Lane Green, the Blue Valley Director of School Administration said. This is mostly due to the district’s improving ability to identify struggling students, Green said, rather than an increase in the number of low income families.

Identifying economically disadvantaged students is not always easy. Although the district aims to provide families with resources, it is the family’s decision whether to reach out. Many simply do not want the district’s assistance, Green said, for reasons which could include privacy, feeling embarrassed of their situation or even pride. Other times, some families are desperately willing to seek any form of help available to them.

“I’ve had mothers and fathers on the phone crying because they were so appreciative. They were scared to death that their kids weren’t going to be able to go to their Blue Valley school anymore,” Green said.

While it isn’t the district’s obligation to reach out, teachers are trained to identify signs of financial distress, Green said. Constant signs of sleep deprivation, hunger or bad hygiene can lead teachers to believe a student may be struggling. Teachers can get in touch with the student’s counselor, he said, who may reach out to the administration. The administration can then take it upon themselves whether to discuss the situation either with the student or the student’s parents.

BVNW social worker Anyssa Wells said financial challenges can also impact a student’s willingness to excel in academics. When the uncertainty of where their next meal is coming from or whether they’ll have a place to sleep that night is the student’s biggest concern, learning can become less of a priority, Wells said.

“If someone’s already working, I mean, their main priority isn’t necessarily get a diploma to then go on to college. It’s probably just to get a job and hopefully a diploma to then further themselves in the workforce.” Wells said.

Senior Dylan Colle said his family has never had a lot of money. Living with his mom, who works two jobs as a hostess, and his brother, Colle works as a soccer referee, referring about 14 hours each weekend.

Although Colle said his financial situation has yet to pose any major issues at school, he said a lot of people fail to acknowledge how significant college opportunities are. As a member of the BVNW varsity soccer team, Colle said he must rely on student loans to pay for college in addition to sports scholarships as he plans to potentially play soccer in college.

An insufficient income has also shaped Colle’s perspective about money as he said he tries to avoid splurging on day-to-day expenses, such as food or other unnecessary expenses.

“Don’t take it for granted and appreciate it.” Colle said. “Just because you’re well-off, doesn’t mean everyone is that fortunate.”

Currently, the school’s means of assisting students financially is limited. Amy Pressly, the BVNW principal, said the school has to provide equally for every student. This means that in order to provide equal access to all students, BVNW cannot offer financial aid from its own pocket.

“I think they work very hard to not look different, whatever that means, and whatever they have to do to do that,” Pressly said. “So we, as a building and as a district, continue to look at, what are we providing for kids? And are we providing things in a way that they have equal access to all kids?”

In the past, programs initiated by the Booster Club have aimed to help BVNW students facing financial struggles, but Pressly said they have phased out due to pressure from the district to provide equal access to assistance.

“I get why the rule is in place, but it makes it tough when you have kids in need and there’s not a whole lot that we can do as a school to help them.” Pressly said. “That’s why we’re trying to figure out… kind of a backdoor way to make it work.”

One way they have found is to provide food packs each week through Community for Kids, which aims to help the students within the Blue Valley community who are unsure where their next meal is coming from. The organization began with Indian Valley Elementary, in order to support the large population of food insecure families within the school. The program soon spread to Northwest and was distributing a total of 60 packs throughout the district. Today, the organization works with 28 schools in the district, issuing 295 food packs weekly. According to Community for Kids, one in 12 Blue Valley students currently have uncertain access to food, and BVNW and its feeder schools account for 22.3 percent of the food packs given out each week.

“The awareness has changed significantly; when we first started, people had no idea if there were any hungry students,” Community for Kids co-founder Sherry Owens said. “It’s even still difficult, because we live in Johnson County that people are still not aware of the need. But it’s something now that people are really opening their eyes to.”

Such organizations are also present within BVNW. Last month, Lauren Crouch, the BVNW academic interventionist, received a $2000 grant from the Blue Valley Education Foundation to build a cabinet full of essentials such as deodorant and shampoo that will be available to students. The cabinet’s purpose is to alleviate the need and cost of essential items, Crouch said, whether a student can’t afford it or simply forgot an item one day.

“I think every kid should have the ability to feel comfortable and feel like all of their needs are being met so their educational needs can be met as well,” Crouch said.

On the other hand, student’s needs are not limited to everyday items. A number of students are also in need of adequate housing. Green said there is a minimal amount of affordable housing for low income families within the district, two of which include Springhill Apartments, which is in the BVNW boundaries, and Arcadia at Overland Park. Because of this deficit, Green said families facing financial struggles often have to reestablish themselves outside of Blue Valley. Once they have a house or apartment in their name, Green said they can finish the school year in Blue Valley, but would have to move to a school in their new district.

“

Because most of the wealthier kids and more upper middle class kids all hang out with each other, a lot of times they don’t see the struggle [others go through].

— Naomi James

Those who cannot afford low income housing may be subjected to homelessness, Green said; a reality to some students and families within the district. According to information provided by the district, 112 students currently lack adequate and regular nighttime residence.

“The biggest challenge we have is getting people to understand that there are actually homeless people in Johnson County,” Green said. “They have trouble believing the Blue Valley School District has homeless kids, and especially the numbers that we have, but we do. Everywhere, there’s homelessness, and we’re not exempt from it.”

To relieve students of some of the financial burdens of homelessness, the Mckinney-Vento Act was created by Congress, allowing the 1,355,000 students identified as homeless throughout the country in 2019 to remain at their schools without required fees.

A free public education can cost more than $300, excluding non required fees such as yearbook, meals, school activities and electives, adding up to more than $500 per student.

The Mckinney-Vento Act can forgive the required fees and provide students with free breakfast, lunch and transportation to school. However, Green said they cannot provide aid for non required fees. The program, Green said, is relatively unfunded as the district only receives a small amount of money from Title 1 funding, intended to help at-risk students from low income backgrounds. Due to this, Green said they rely on community organizations.

“[The funding] doesn’t scratch the surface [of] what it costs to provide the services to our kids,” Green said. “However, I want to make this very, very clear: that’s all right. You know, because we’re about all kids. All means all. Each kid means each kid. And we want to help every single kid in our district and so we sometimes have community partners that help us with stuff, but it’s more than worth it to make sure these kids can continue to get a great education.”

To make up for what the district cannot provide, students have taken the issue into their own hands. Student Government holds an annual philanthropy drive which aims to collect items from the student body and donate them to local organizations. Sarah Derks, the StuGo sponsor, said four years ago, they collected $4000. This year, the number dwindled down to $100.

The culprit behind such a low number, she said, may be that they’re asking for too much by constantly demanding items for various charity drives. Another alternative reason may just be a prideful or careless mindset, she said.

“As student government, it’s frustrating that the first thing that comes to mind is that in order for someone to donate, we have to give them something in return. But you would just think that maybe that would be an encouragement,” Derks said.

The truth is, the number of cash-strapped students in the district is growing. Because of this, there is still a need for more awareness, Green said, of community organizations that support families in the area and work toward helping students receive aid.

Every student has a story, Pressly said. Although financial aid limitations for the school do exist, delving deeper into what is happening in their students’ lives has become a new mission for the staff, she said, in hopes to provide as much assistance as they can.

“There’s story after story of successes of kids who’ve overcome obstacles, not only here, but across the country,” Pressly said, “I don’t want any kid to ever feel like they’re defined by their socioeconomic background.”