At five years old, Sophomore Ella Moore had to be rushed to the hospital and put under anesthesia. When she woke up, she had a port in her collarbone and had been diagnosed with acute lymphoblastic leukemia, or ALL.

ALL is a cancer of blood and bone marrow. According to the Mayo Clinic, it is the most common cancer among children.

Moore said she was treated with chemotherapy from ages 5 to 8 and did not fully complete remission until age 12. She said this treatment process made attending school very difficult, especially after she changed schools in the second grade.

“That’s when I was really sick, so I missed school every Wednesday, and I [felt] more sick, I just wouldn’t go at all. It was weird at first,” Moore said. “I think it’s just hard to understand cancer at that age, so it was a lot of trying to explain it [to a child].”

Though Moore did experience some difficulty adjusting to her new lifestyle, her mother, Julie Moore, said the family had various support systems in place such as Moore’s classmates, Julie’s coworkers, family members and friends. Julie said her workplace, Moore’s school, was quite accommodating to her child’s condition.

For example, Moore would often have to go to her mother’s classroom to rest in order to deal with the exhaustion brought on by her treatment. Julie said her students were accepting and kind to Moore when she visited her mother to take a nap.

“My students were super supportive. Everybody just always covered for us, and they were always ready to support us,” Julie said. “All of my students would be so quiet and respectful and sweet. They just wanted her to be OK.”

Outside of receiving support from coworkers and loved ones, families with a child who has cancer can receive support and answers for their child’s condition through community organizations. After Moore’s initial diagnosis, her parents got a call from Braden’s Hope, an organization named after cancer survivor Braden Hofen who was diagnosed with neuroblastoma at three years old. According to Executive Director Kim Stanley, Hofen’s mother, Deliece Hofen, was fighting breast cancer at the same time as her son, even having chemotherapy on the same days in two different hospital locations.

While her son was undergoing treatment, she noticed that there was less research being done for childhood cancers compared to cancers that are more common. Stanley said Hofen found only 4% of funds were allocated to childhood cancers, so she decided to start her own organization.

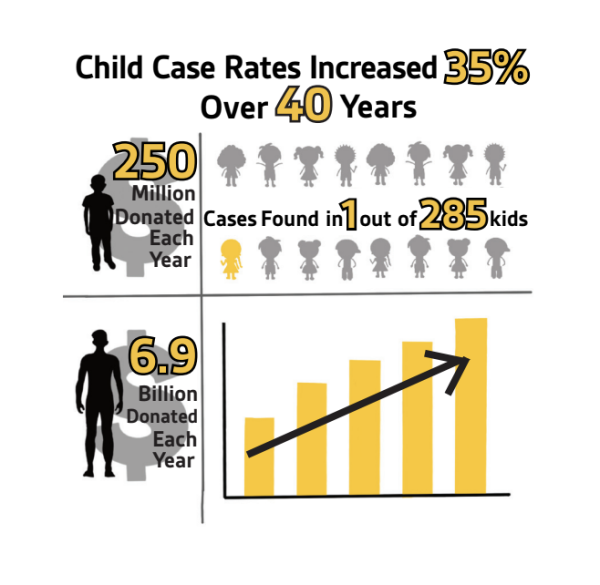

For comparison, $6.9 billion is donated each year to adult cancer research, according to American Institution for Cancer Research and $250 million to childhood cancer research, according to Little Warriors Foundation. Childhood cancer can be found in one out of 285 kids before their 20th birthday in the U.S. That is 300,000 children every year. Childhood cancer rates have increased almost 35 percent over the last 40 years, according to the American Childhood Cancer Organization.

Since its founding in 2010, Braden’s Hope has been able to raise $5.5 million for childhood research grants with their partners, Children’s Mercy Research Institute and The University of Kansas.

“We aim to fund as much research as possible so that we can level the playing field for children and families who fight cancer,” Stanley said.

Some students choose to join the cause by participating in Gold Out KC, a local organization created in 2016 to support children battling cancer. Co-president of the Blue Valley Northwest chapter, senior Divya Subramoni said she wanted to continue the club’s mission to raise awareness and money for research and work with St. Jude’s Hospitals to ensure no family has to pay for housing and treatment.

“I think it’s an important thing to raise awareness for [childhood cancer] because [while] losing anyone is a tragedy, losing a child [feels] like something different,” Subramoni said.

At Northwest, she said the club will host fundraisers at sporting events to raise money and educate the community about childhood cancer.

Though many are working to raise awareness about childhood cancer, it is not possible to fully understand one’s personal experiences. BVNW social studies teacher Lauren DeBaun said she was diagnosed with Hodgkin’s lymphoma during her sophomore year of high school. DeBaun said hearing her diagnosis was quite difficult to comprehend, especially as a student athlete.

“Logically, it didn’t make sense to me and emotionally, none of it really clicked with me,” DeBaun said. “My goal in life was to play college basketball, so in my teenage mind, this was getting in the way of my dreams.”

According to DeBaun, the changes she experienced during her treatment took away from her personal identity and affected the relationships she had in school.

“Who I thought I was in high school had to do with three specific things about myself: my height, my curly hair and being a basketball player, so I had most of my identity completely stripped from me,” DeBaun said. “I found that [people] who I thought were my friends were not really my friends, and a lot of people stopped talking to me.”

A cancer diagnosis can force people away from personal interests, hobbies and life. Moore said her time spent in the hospital caused her to miss important events and holidays. A time that stood out to her was when she was rushed to the hospital on Dec. 21 and missed her family’s Christmas at her grandma’s house in Nebraska. Julie said they missed being with family and friends during one of their biggest annual celebrations.

“Not only did we miss a holiday, but it was a really scary time because her kidneys had stopped functioning, so it seemed like her organs were failing,” Julie said.

After 10 days of fear and uncertainty, Moore was released from the hospital on New Year’s Eve. Julie described this period as being highly emotional, awful and stressful.

Now, 10 years later, Moore is cancer-free; however, it is still a part of her life because she has a higher risk of getting cancer later.

“Kids who get chemotherapy and survive cancer when they’re young have a [higher] chance of experiencing some other sort of cancer in their life,” Julie said. “It seems unfair.”

Moore said even today going to the hospital can be scary and even cause feelings of PTSD from all her visits as a child. After she was first off chemo she was put in remission and had monthly visits up until last year. Blood testing and hospital visits will always be a part of Moore’s life along with the emotional trauma she went through.

According to DeBaun, childhood is an important time in life and a cancer diagnosis can have a significant effect on their development.

“Childhood and adolescence is when we as humans do the most developing, physically, emotionally [and] mentally,” DeBaun said. “To have something like [cancer] on top of just the normal development of a child is traumatic, and I think there’s some cancers that need a lot more research behind them.”