Anna Shaughnessy and Lindsey Farthing

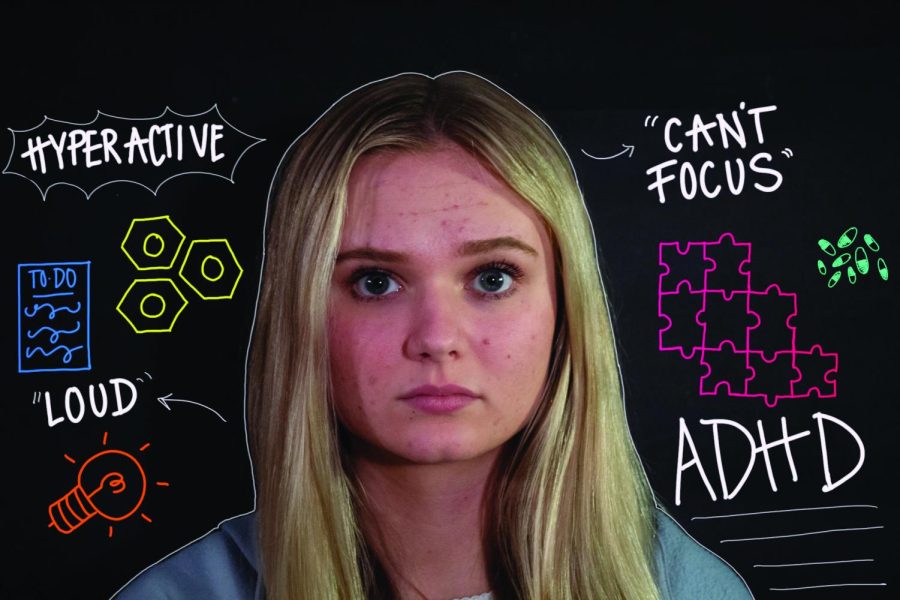

Senior Kimberly Gibson discusses how having ADHD has affected her outside of the learning environment. “It also affects your self confidence too,” Gibson said. “Because you can’t really control how hyper you are.”

Neurodivergent

Students with learning disabilities bring attention to the disadvantages they face in the Blue Valley education system

Although she was diagnosed in November, senior Kimberly Gibson said she always knew she had attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) as she said she was always more talkative and hyperactive than the average kid.

“I’ve always been this way since I was a little girl in elementary school. I used to get in trouble a lot for talking too much,” Gibson said. “Teachers used to think that I was being disrespectful, but in reality, I just couldn’t control it. It’s just how my brain worked.”

Similarly, freshman Brooke Troppito, who also has ADHD, said talking too much is one of the main things she experiences with ADHD.

“One of the hardest things is sometimes I talk too fast or I talk too much. I don’t have some social cues that I probably should and eye contact is difficult,” Troppito said. “And, I get distracted very easily and I lose my train of thought very easily.”

Before she started taking medication for her ADHD, Gibson said it was hard to focus in school and absorb information in an eight-hour day.

“[I had] to work a lot harder to achieve good grades than somebody who doesn’t have ADHD,” Gibson said.

ADHD, Gibson said, also affected her work performance as it prevented her from completing tasks. She said it impacted her confidence during moments such as these as she was unable to control how hyper she was.

“It’s kind of stressful when you’re in a school environment and you have to act really calm and you feel like you can’t be yourself,” Gibson said. “But then when you are acting like yourself, it’s stressful because you don’t feel like you fit in with everyone else.”

For these reasons, Gibson said she grew to hate school.

“You don’t even get a chance to move around except for a five-minute passing period,” Gibson said. “But that’s definitely not enough for somebody with ADHD because I feel like I always need to be moving around.”

Troppito agreed that navigating school as a student with ADHD is very challenging.

“The biggest challenge is definitely school or social gatherings because they make me uncomfortable and I’m not a fan of eye contact,” Troppito said. “But also, school is very difficult because if I’m not super interested in it, then I’m not paying attention at all.”

The school system does not support neurodivergent students well enough, according to Gibson.

“There’s got to be a lot of changes made to the school system to incorporate everyone’s needs and feelings for the school to feel comfortable,” Gibson said.

According to Gibson, the school system is geared toward a particular kind of student who can sit in school for eight hours a day and focus on things they do not care about, while still being able to succeed.

“I definitely wish they would incorporate more things for students with ADHD so they could be able to move around [and] have breaks every so often,” Gibson said.

The main resource Troppito said she has at school to help her with her ADHD is the gifted program.

“I think gifted is a really good way for me to be able to do stuff because [the teachers are] very accommodating and they’ll help you with anything and if [I] need to leave a space…I can just go in there,” Troppito said.

Junior Nia Bender agreed with Gibson, saying that school is not designed for every kind of student which is partly why, as a fifth-grader, Bender transferred to Horizon Academy, a school for students with dyslexia and other language-based learning disabilities.

“I didn’t mind transitioning to that small private school, because I wasn’t happy at the current school [Indian Valley Elementary] that I was at because I want to learn, I want to meet my full potential,” Bender said. “And [Horizon Academy] definitely helped me reach my full potential and helped me to be the extraordinary student that I am today.”

Although her old school placed her in a special education program, Bender said Indian Valley Elementary, a feeder school for Northwest and the school she attended before transferring to Horizon Academy, did not do a sufficient job of helping her cope with her four learning disabilities.

“It felt like a waste of my time and like I could be doing other stuff to help me with this and help me improve, but instead you’re just having me sit here on my iPad the entire day,” Bender said. “It felt like a huge waste of my time and [was] very unhelpful.”

In fact, Bender said she would fake being sick so she would not have to go to school.

“In my mind, I’m like, ‘I’m not smart enough to do this work. I don’t know how to do it.’ So I’m just not even gonna try,” Bender said.

As a fifth-grader, Bender said she was at a third-grade reading level, but by the time she left Horizon Academy in eighth grade, she was at a tenth-grade reading level.

“While there wasn’t a great opportunity to be social, [the school] definitely help[ed] get the kids one-on-one time, which is what I think the public schools were lacking,” Bender said.

In Blue Valley, one teacher has to deal with at least 24 students already which makes helping all of them with their individual needs difficult, according to Bender.

“There’s no way that they [teachers] can get through each one [kid] individually and get them the proper and specially designed help that they need,” Bender said.

After she graduated eighth grade, Bender said she decided to return to public school because she made the progress she needed to. At first, she said the transition was very overwhelming due to a large number of students and differences in teaching styles.

“We had to devise a 504 plan for me to help me get through [my] struggles and challenges and help me be successful,” Bender said.

A 504 plan is a formal plan created by schools to help students with disabilities receive the support they need. For Bender, she said this plan included accommodations such as receiving more time on tests and getting the teacher’s notes to help with her auditory processing disorder. However, Bender said during the required evaluation, the subjects she learned about in the study skills class like organization and planning, were unhelpful as she already learned about them at Horizon Academy.

“After one semester of it, I’m like, ‘mom, I need to get out of this class. They’re not helping me. This is a waste of my time,’” Bender said. “‘I don’t need to work on my organization and my planning and how to do self-advocacy.’”

To improve how they teach Neurodivergent students, Bender said all teachers at Northwest should be trained by professionals that deal with learning disabilities daily.

“They need to change the curriculum and they need to make it more individualized and not just be like here, here’s a program that you can go on that will help you,” Bender said. “You need to be taught by an actual person that knows what they’re talking about.”

Jennifer Luzenske, the Director of Curriculum and Instruction for the Blue Valley School District, said that teachers have been trained to teach reading in a new and more effective way that benefits students with dyslexia, such as Bender.

“Any accredited school in the state of Kansas is now implementing what is called structured literacy as the approach for teaching reading,” Luzenske said. ”It is particularly advantageous for students with challenges in reading, including students with dyslexia.”

Luzenske said teachers have many resources to strengthen their knowledge of dyslexia, and how to assist students with dyslexia, which in turn benefits the students receiving the instruction.

“There [are] a lot of phases to training the faculty so we have professional learning with teachers on district professional learning days,” Luzenske said. “We have reading specialists that are right there in the buildings that can provide support and professional learning for teachers on demand.”

Along with students, staff members and other adults in the community navigate life while being neurodivergent. Math teacher Nick Titus has dyslexia. He said he was diagnosed as a junior in high school but has experienced its effects his entire life.

Titus did not attend schools within the Blue Valley District, but throughout his schooling, at St. Thomas Aquinas in Wichita for elementary and Kapaun Mt. Carmel for highschool, he said he was not taught to read in a way that was effective for him.

“I struggled a lot with the ways that they teach you to read, and English itself is a difficult language because of the inconsistent rules for phonics and spelling and things like that,” Titus said.

However, Titus believes this issue has improved recently and discovering dyslexia in younger students has received more attention within the Blue Valley community.

“I think they’ve been doing a better job of identifying students earlier and they’ve made an effort as a district, recently, to emphasize that which I think is a good thing overall,” Titus said.

Colleen Zink, the Dyslexia Coordinator for the Blue Valley School District, said there has been more awareness spread about dyslexia within the education system which can lead to more assistance starting earlier in life.

“I think there definitely has been an awareness made of what characteristics of dyslexia are,” Zink said. “So if you understand what to look for, then you’re going to be able to help the students differently than you might have in the past.”

With dyslexia being addressed at a younger age, students may face opinions from peers. Titus said one such opinion deals with associating learning disabilities with a lack of intelligence, however, this is not true.

“People interpret any sort of learning difference or difference in understanding as an intellectual difference,” Titus said. “[But] there’s not a correlation between intelligence and dyslexia or [other] learning differences.”

Along with the misconception that learning disabilities mean a lack of knowledge, Gibson said she also encounters people thinking she is trying to be disrespectful or a trouble maker, but they do not realize she is someone who is struggling to focus and stay on task as it is a part of her ADHD. She went on to say that this is just how her brain is wired and it is not something people with ADHD can control unless they are medicated.

“Each person learns differently and even if it’s not the way that you learn, that doesn’t mean that it’s weird or different,” Gibson said.